MMC is a broad heading that is used to define and categorise construction efficiency by transferring labour-intensive on-site construction methods to a controlled factory assembly process.

At Douglas and King we can see the advantages of MMC in all areas of a development. We embed MMC into all of our design processes spanning the full RIBA Plan of work.

The many benefits offered by Modern Systems and Construction Methods can be summarized in these key points:

Greener

Factory controlled processes reduce waste in time and materials.

Faster

Are more efficient meaning site construction time is greatly reduced.

Smarter

Ensures better construction quality management.

Safer

Eliminates on-site construction hazards

Adaptable

Factory construction allows the same level of flexibility and adaption as a site built project

What is MMC?

The UK Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government have published a Definition Framework that classifies 7 categories of off-site construction and spans all types of pre-manufacturing, site based materials and process innovation.

Here we outline how to take full advantage of employing the wider agenda of MMC in a development project.

1. MMC in appraisal and delivery

Development projects today require design input from many different experts. These include a core team of consultants along with various specialist reports along the way. A simplified project delivery is design led with online co-ordination and planning.

The MMC driven planning and project management systems we use chart a route though the RIBA Plan of Work stages so that everyone involved shares a common goal. We build MMC into our Appraisal system, the backbone of our project management process from the initial stages of our appointment to client handover.

2. MMC as a design tool.

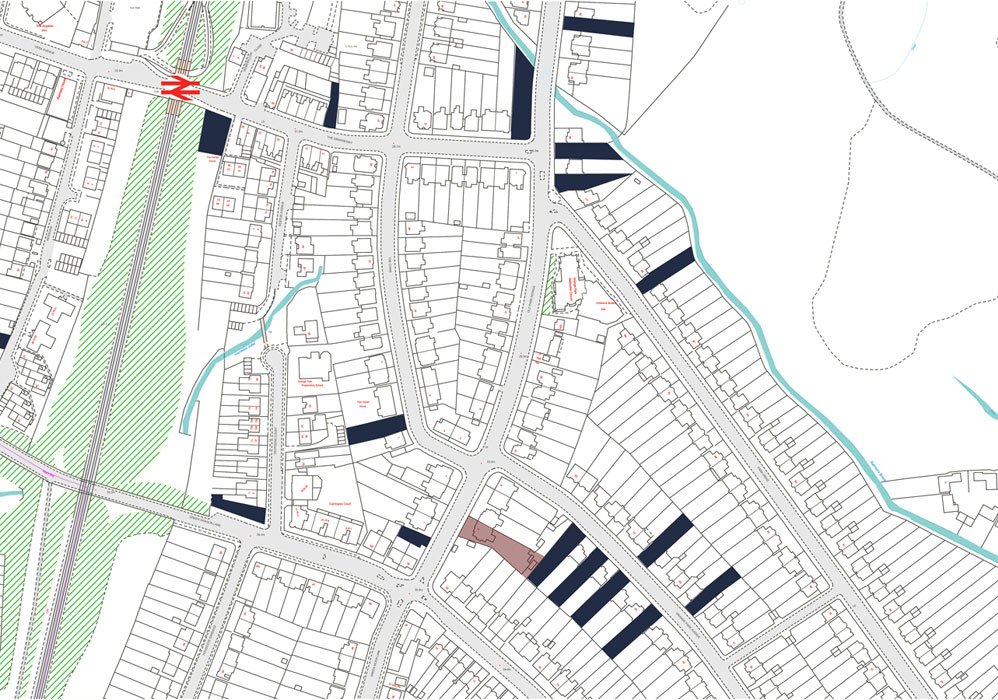

Our BIM CAD System allows us to easily balance all of the design drivers that we use to conceive and test site constraints to maximise development potential. Core consultants within a design team work on a common online CAD and data file and our clients and investors always have access to our snapshot reporting facility.

All MMC manufacturers have BIM capabilities that talk to our own computer systems. This means we are always fully engaged with industry developments including updates to product performance and specification, and greater efficiency in all areas.

We can specify adaptable factory built systems so that we can create buildings that are of the highest quality, fit for purpose and built to last.

3. MMC in Infrastructure, Ground Works and Contract Administration

Getting out of the ground is a huge challenge in any construction project. Whilst MMC systems on the market today commonly focus on above ground construction with varying levels of completion there are many MMC products and design methods we can employ in, for example, the connection of utilities, landscaping and roads and foundations and below ground structures.

Working with leading Structural, Civil, and Environmental Engineers and through BIM Software we are able to establish a co-ordinated, environmentally sound and cost-efficient construction system for the major elements of a building. In a large part, we can include elements that are not commonly conceived to lie within the MMC package.

MMC eliminates many of the hazards that befall the construction process when on site and increases the efficiency of contract administration.

4. MMC – Onsite construction, the main systems available

We have written elsewhere about the main systems of MMC available for MMC construction along with their varying levels of completion. See our blog

‘Transforming construction in the digital age’

Timber framed construction has been widespread in the UK building industry for thousands of years. MMC allows us to create the same structures in a better way, with all components, from insulation to surface finishes, applied in factory controlled conditions.

We work with suppliers and fabricators at an early stage so that we utilize systems that best suit the needs of a site or a building and which champion financial and environmental efficiencies.

5. MMC and the climate emergency

As owners and designers look for more sustainable designs for improved environmental impact, modular construction is inherently a natural fit. Building in a controlled environment reduces waste through avoidance upstream rather than diversion downstream. This, along with improved quality management throughout the construction process and significantly less on-site activity and disturbance, inherently promotes sustainability. High quality, sustainable, innovative, efficient, cost-effective, and shorter time to completion.

Well designed buildings benefit from a connection with the natural environment and have a minimal impact on the circular economy (i.e. they do not need to be replaced or face a major upgrade within a few years).

6. MMC as a positive outcome

As Architects and Project Managers we fully embrace the benefits of MMC to create better buildings and environments. MMC does not mean that all buildings will look the same, factory systems are infinitely adaptable and offer huge improvements to the built environment whether they are residential, public realm, or otherwise.

Through our connections with Max Farrell and the London Collective Douglas and King are currently working on a new town development within the Oxford to Cambridge Arc that is built around a National Centre of MMC Excellence. The MMC Centre will be part of the DNA of the new town and will be a place where leading manufacturers and suppliers, along with academics and designers, can showcase their technology to contractors, stake holders and to end users.