Douglas and King are currently involved in the planning and design of small, medium and large-scale housing developments. Whilst we have completed many residential projects in the past, including multiple home models, these have mainly been located in densely populated urban environments.

The challenges of creating a new community within a non-urban setting are multiple. Fundamental to our strategy is the process known as Place-making.

We have looked at exemplars and learned from them – we understand how successful and sustainable communities can be developed through the fabric and identity of ‘place’. As architects we have a social and professional responsibility to design the best we can for the aspiration and needs of those we are designing for.

Central to our thinking is how can we design authentically for the community that will live, work and play in this new neighbourhood, what will nurture the elusive spirit that binds rather than separates? The answer is Place-making.

What is Placemaking

Place-making is an inclusive approach to the design of new environments that create a unique identity – a shared sense of community, a place of being and belonging to – in surroundings which improve the quality of life for the residents.

For each of the housing developments we are involved with we look at how people will interact and how we can design for the benefit of all. This means we must create an identity and a sense of place for the overall development and appraise the individual components that will give the development the ‘dynamic’ we seek to achieve.

We attempt to apply the Principles outlined in the RIBA publication ‘The Art of Building a Garden City’. The Authors state that the garden city principles are not a ‘blue print’ for new developments but do outline a successful approach. Each principle can be beneficial to a smaller development if implemented on its own, however to maximise the potentiality for place-making it is important to incorporate as many as possible.

The core principles of sustainable 21st century communities

1. Land value capture for the benefit of the community

2. Strong vision, leadership and community engagement

3. Community ownership of land and long-term stewardship of assets

4. Developments that enhance the natural environment and provide comprehensive green infrastructure networks and net biodiversity gains, and that use zero carbon and energy positive technology to ensure climate resilience

5. Strong local cultural, recreational and shopping facilities in pedestrianised zones

6. Integrated and accessible transport systems, with walking, cycling and public transport

7. Mixed tenure homes and housing types that are genuinely affordable

8. A variety of employment opportunities within easy commuting distance

9. Beautiful and imaginative homes and gardens, combining the best of town and county to create healthy communities including opportunities for the cultivation of vegetables, fruit and foodstuffs

Current partnerships and policies

It is a regrettable fact, but one nonetheless, that the supply of new housing in the UK is currently indebted to private sector developers. This means that the principal business model/motivation of the organisations involved is not for the common good – it is for profit.

Even the most exemplary and conscientious of housing developers have to provide a return for investors and shareholders that can be measured in monetary terms above all else.

In its 2016 publication, ‘Development: The Value of Place-making’ the property consultants Savills explain that spending on infrastructure, local amenities and public spaces creates better places.

It goes on to describe how the Land Value Uplift through place-making can be increased by as much as 25% and contends that the Land Value Uplift enables the delivery of the kind of neighbourhoods that communities want.

The evidence is provided by financial outcomes from two developments, Poundbury, Dorset and Brooklands, Milton Keynes, both of which are exemplary place-making projects and have increased house values by up to 91% over neighbouring, less considered, housing developments.

10 Principles of Placemaking

The Berkeley Group categorise the following key ingredients in their publication ‘Principles of Place-making’:

Planning

The Correct Location

Partnership Working

Listen and Relate

Design

Bespoke design

Mixed use and mixed tenure

Low carbon

High quality public realm

Implementation

Attention to detail

Each phase is a whole

Invest in management

The Golden Rules Applied

Below we give two examples where we have applied place-making principles to create successful small, medium and large scale housing development.

Goffs Oak, Hertfordshire

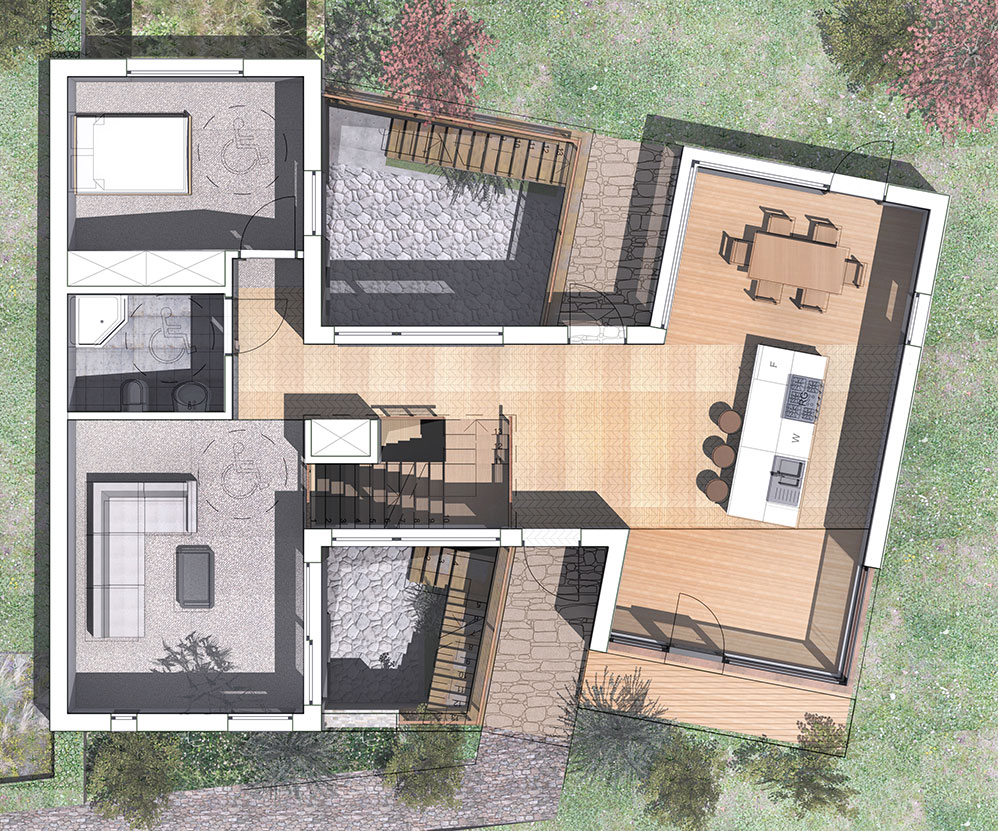

This is a small development of 10 residential units and is a perfect example of how place-making, as the core value, is delivering a new sustainable community within a developer led project. The project has from the outset been conceived with the objective of achieving mixed tenure homes and mixed housing types.

The key place-making features we have applied are:

- Designed to encourage community engagement

- Substantial areas of shared land and space within the development which are jointly owned

- Mixed house types, sizes and tenures

- Vernacular building types, and each designed individually to respond to location and position

- Gardens and shared areas landscaped to enhance the natural environment

- Local shops within walking distance

- Respect and response to the local environment

Chadwell St Mary, Essex

Chadwell St Mary is a development to the north of the Essex town of Tilbury that is being designed and planned using the principles of place-making.

The impact of placemaking within the socio-economic equation

Within the interaction of social and economic progress housing plays a vital role. We live in a pluralistic society so the creation of healthy neighbourhoods is of primary importance. Strengthening the connections between people and the places they live in and share is central to place-making and to accepted socio-economic goals.

A vibrant, attractive, and secure neighbourhood will attract a mixed demographic and will be of benefit to the overall community strategy of the area. It will also attract employers as it offers them a workforce with a range of ages, skills and abilities.

How does the creation of successful neighbourhoods through place-making increase development profits?

When people go to look at a property as a potential home they prioritise certain ‘values’ – some of these are commonly shared and some are not.

Shared values will almost always include:

- A safe and secure neighbourhood

- Access to schools, shops, recreational areas, public transport

- Employment opportunities

- Commuting options and services

- Quality of life

Estate agents drive the property market and developers are currently driving the housing market. In each case the primary motive is to increase the commission value and or to optimise the profit value for their shareholders. The home-buyer or home-owner isn’t quite a Pawn in their game of Chess but they are certainly not as powerful as the Knight or the Queen.

Developers and estate agents will sell the concept of ‘lifestyle’ over and above the aesthetic of the development’s design or its community and environmental attributes.

As architects commissioned to design these new housing developments it is important that we ‘sell’ hard the benefits of successful place-making and that the goal is long-term not short-term. We hope to share this sense of responsibility for the communities we develop with our developer partners and to embrace a collective ambition to:

- create inclusive communities that will endure beyond our lifetime

- yield the investment potential that the developer requires

- contribute to the quality of life for those who live in the homes we design

- build homes that are authentic, have longevity and flexibility

- work with the most sustainable methods of construction, insulation, ventilation, etc

Other accompanying blogs in this series are:

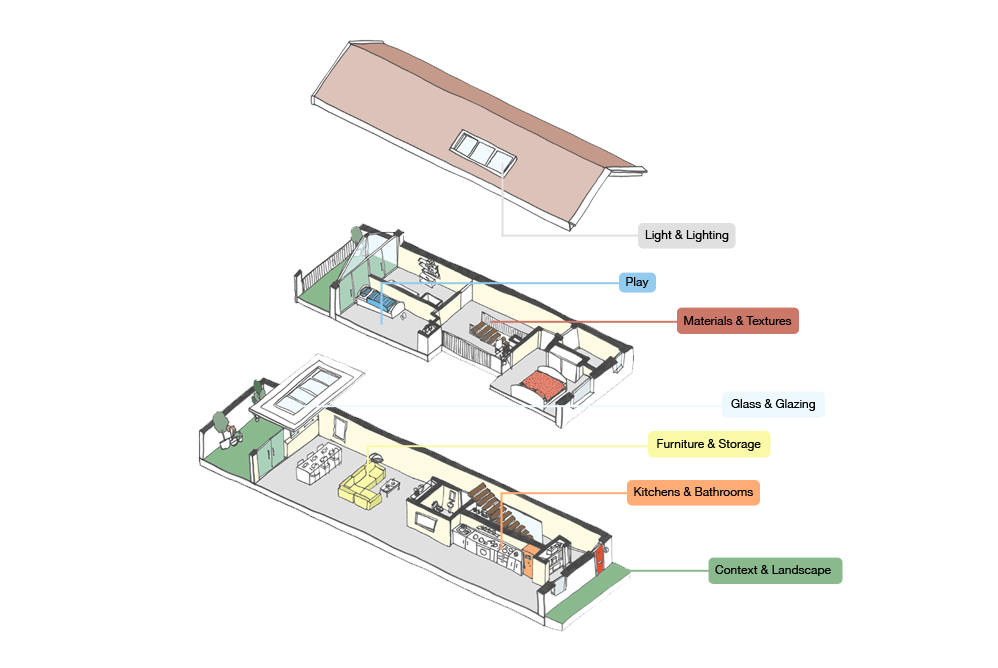

Designing Homes – The Argument for an Authentic Approach

Evolution of The House Type

Modern Methods of Construction